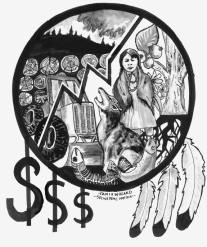

Harvey is referring to the often violent and predatory process by which multinational corporations, backed by capitalist states, expand their role and influence by dispossessing people of their land and livelihoods.

Dispossessed indigenous peoples, small farmers and peasants are forced to turn to the labour market in order to survive, creating a cheap pool of labour for corporate enterprises to exploit. At the same time, corporations can gain unhindered access to the resources on the now unoccupied land – agricultural land, minerals, lumber, real estate, oil, even commodified nature (parks, tourism). This is a central process by which capitalist imperialism operates.

The Canadian state’s predatory historical relationship with indigenous peoples provides a sharp example of the dynamics of accumulation by dispossession. This involved a variety of brutal processes, including the military defeat of the Métis-led national liberation struggle in the then-Northwest Territories, the apartheid Indian Act and its Pass Laws, the attempted cultural genocide of the residential schools and the ongoing abrogation of First Nation treaty rights.

Land was taken for the development of capitalist industries, while indigenous people were “encouraged” by the Indian Act and residential schools to stop traditional subsistence and cultural practices in order to engage in the more “civilized” labour market.

Neoliberalism

This agenda has intensified in the neoliberal period. Neoliberalism is the ruling class’s response to the economic profitability crisis of the 1970s; it involves restructuring labour relations in favour of business, gutting the welfare state and privatizing public services.

The success of neoliberalism is in large measure contingent on the increased commodification of indigenous land and labour, turning it into something to be bought and sold on the market.

Nevertheless, large segments of the indigenous population have successfully resisted full integration into market relations in their territories. The frontier of capitalist expansion, in the eyes of the state and business leaders, still has significantly further to go in Canada.

In a context in which, on the one hand, corporations are aggressively pursuing a cheaper and more flexible labour force as part of its agenda of neoliberal restructuring, and, on the other, the non- Indigenous Canadian-born population’s fertility rates remain low, indigenous labour has become highly valued. This is clearly expressed in policy documents produced by the Ministries of Indian and Northern Affairs, Industry and Natural Resources.

Sociologists Vic Satzewich and Ron Laliberte note that reservations were originally organized as a pool of cheap labour to be drawn upon when needed, and are still viewed by government as such. As one recent Indian Affairs and Northern Development study stresses, “The Aboriginal workforce will grow at twice the rate of the total Canadian labour force in the next ten years.”

But to the chagrin of the state and business, many indigenous people and communities continue to resist full absorption into capitalist relations. Government documents salaciously note the potential indigenous labour supply and the wealth of resources on indigenous land, but they also often reflect on the difficulties of getting indigenous people to sell their labour for a wage or willingly permit the penetration of their communities by resource companies.

Mining and “Development”

The mining industry provides a stark example of the intensifying pressures on indigenous lands and communities. Over the last decade, mining companies have been expanding their activities into regions of the country where capitalist development has hitherto been limited. Exploration has been increasing in northern and interior British Columbia, the northern prairies, Ontario and Quebec, the Yukon, Nunavut, and especially the Northwest Territories since diamond deposits were discovered there in the early 1990s.

The Mining Association of Canada notes that, “[m]ost mining activity occurs in northern and remote areas of the country, the principal areas of Aboriginal populations.” Natural Resources Canada reports, meanwhile, that approximately 1200 indigenous communities are located within 200 kilometers of an active mine, and this will only increase as exploration intensifies.

The location of the majority of mining operations is significant, because it brings the industry squarely into conflict with indigenous land rights. First Nations may claim title to much of the land mining companies seek to exploit, or oppose mining developments that will cause ecological damage to traditional territories and subsistence patterns.

But the location of mines is also very significant in a context in which, as industry and government studies indicate, mining is facing a labour shortage. Indigenous labour, in turn, is explicitly identified as central to the expansion of the industry. “Workforce diversity,” as one industry-wide study expresses it, with a healthy dose of liberal veneer, is a necessity for the future success of mining.

This is driving the growing conflicts between mining companies and First Nations like the Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug (Northern Ontario), Kwadacha (B.C.), Tlatzen (B.C) and Kanien’kehaka (Quebec) among many others. Indeed these are the tip of the iceberg, and battles like these will continue as mining companies intensify the expansion of their ecologically violent practices into indigenous territories, threatening ecosystems and the communities living in them.

Strategies of Dispossession

In response to indigenous peoples’ general unwillingness to prostrate themselves to capitalism, the Canadian state is engaged in a sustained effort to dispossess them of their land. This ranges from legal manipulations to outright violence, as the pressures of capitalist expansion over the last two decades have intensified, indeed militarized, the colonial conflict between Canada and indigenous nations.

The formal land claims process, for example, facilitates the expansion of capitalist development onto indigenous territories. It’s extremely slow and bureaucratic, taking up to fifteen years after a claim is initially made before the process is commenced.

That’s at least fifteen years more time for indigenous lands to be whittled away and/or poisoned. Or fifteen years for poverty and frustration in communities to grow, leading to out-migration and making the communities more vulnerable to one-sided deals with corporations.

Furthermore, the federal government has made the extinguishment of Aboriginal title a prerequisite of any land claims settlement they’ll agree to. This involves relinquishing collective ownership over land and subsurface resources of large parts of traditional territories – as is the case with the James Bay and Nisga’a comprehensive agreements.

Extinguishment – a legal form of dispossession supported by Supreme Court decision and pursued zealously by the government – is a major barrier to the fair settlement of land disputes and reinforces the colonial status quo between the Canadian state and indigenous nations.

Even where treaties exist, they are repeatedly ignored and their terms are systematically broken by governments in the interest of economic development or national security. This is the reality underlying the events at Oka (where the local municipal government tried to appropriate land for a golf course), Ipperwash (where the military stole land and physically removed members of the Stony Point community in order to build an army base during the second World War), and today in Caledonia (where housing developers are trying to build on Six Nations’ treaty land).

These are but three of the countless examples of state-sanctioned theft of treaty lands that have gained national attention because of indigenous resistance in the face of serious political and military pressure. In fact, in the Delgamuukw decision (derided by the Right and the business community as unambiguously pro-Indigenous) the Supreme Court actually defends the government’s right to appropriate indigenous land for economic reasons.

Of course, never too far removed from these strategies of dispossession is military force, which we have seen mobilized in recent years at Oka, Gustafsen Lake, Burnt Church and Ipperwash. It also remains a threat at the Six Nations standoff in Caledonia. While the state may wish to pursue its colonial strategy in the tidier bourgeois legal realm, it will make recourse to military violence to enforce its agenda where necessary.

The lesson for the Suretée du Quebec after Oka and the RCMP after Gustafsen Lake was to invest more resources in military weaponry in preparation for future confrontations.

Canadian colonialism – like colonialism around the world – has always had its bloody side. If indigenous nations won’t be compliant, capitalist expansion will be defended by violence.

The agenda of dispossession is not simply the misguided policy of shortsighted or self-interested business or political leaders. It is central to state and corporate relations with indigenous communities, driven by the demands of the capitalist economy and shaped by a deep-seated racist view of First Nations as uncivilized and unwilling or unable to economically develop their territories. This consideration must not be forgotten in the struggle against Canadian colonialism.

Todd Gordon is a member of Toronto New Socialists. He is the author of the books Imperialist Canada (2010), and Cops, Crime and Capitalism: The Law-and-Order Agenda in Canada (2006). A longer version of this article appeared in Socialist Studies (2006).