From the beginning, in the protest literature and language of the ASSÉ-driven mobilization, it was always extremely clear that the strike was not simply about stopping the tuition hike, but also about challenging a neo-liberal model being imposed on Québec society within a global context of violent austerity economics.

Two key elements of the strike that I feel illustrate the sense of radical politics, meaning a political process fighting for systemic social transformation, were the general assembly process and direct actions. The general assemblies actively subverted mainstream conceptions of the democratic process, challenging the western liberal conception of democracy that is often limited to the ballot box, actively expanding “democracy” to equal a hands on participatory process that includes direct votes and active debate by the people directly impacted.

This sharp political tone is rooted in history. Québec’s student strike in 2012 took place after many years of mobilization and also many past student strikes. Calls to abolish tuition fees rang out on the streets during the major social upheaval in the late 1960s and early 1970s, protests that directly lead to the creation of the CEGEP college system and the Université du Québec system, as institutions constructed in response to calls for accessible Francophone post-secondary education of the people of Québec. The process of student mobilization continued, there was a mass student strike in 1974 and again in 1978 that saw hundreds of thousands of students striking to fight for the total abolition of tuition fees, a process of mobilization that continues until today.

There were also powerful strikes more recently where a contemporary militant tone to student actions really took shape. The 2005 student mobilization in Québec saw the beginning of the carré rouge [red square] as a symbol, but also direct action and larger perturbation économique, or economic disruption tactics, being a central part of the ASSÉ (Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante) action plan.

There were also powerful strikes more recently where a contemporary militant tone to student actions really took shape. The 2005 student mobilization in Québec saw the beginning of the carré rouge [red square] as a symbol, but also direct action and larger perturbation économique, or economic disruption tactics, being a central part of the ASSÉ (Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante) action plan.

So in the lead-up to 2012 strike there was a clear and recently implemented tradition of direct action that was an important part of the landscape of action. Many activists supporting the strike in 2012 had participated in the direct actions carried out in 2005 during the campaign to fight against a $103-million dollar cut to the student bursaries program by the Liberal government.

Also I remember a direct action handbook that ASSÉ was passing around to activists, and that was being used at different workshops in the years leading up to 2012. That booklet made it clear I think that ASSÉ had definitively decided that militant direct action was a key part of any strike action strategy. Also the fact that ASSÉ was carrying out many direct action workshops clearly illustrated the radical tone in the student movement.

Within ASSÉ, the broader student movement and Montreal community activist networks that are interrelated, there are countless debates about tactics and strategy. I think that the strike in 2012 created a clear opportunity for many thousands of student activists and supporters to participate in a campaign that included direct action regularly, not one-off actions, but an ongoing process. This was radicalizing for so many because the direct actions placed students in front of a very obvious and violent representation of state power, the police forces.

Beyond direct action, I think what was important about the student strike in 2012 was that it was radical in nature, that the movement was a revolutionary one in many ways.

There were strong elements within the bureaucracy of student federations which were aiming to mount political pressure on the Québec government to win reforms. However, many activists within ASSÉ-affiliated unions built and prepared the strike to confront the neo-liberal machinery of the Québec Liberal government, aiming to take it down, not to reform it.

In this sense the most radical, but also wildly popular aspect of the strike at the peak, was the fact that the student unions were asserting a political power independent from the state. The student strike really built actions based on the concept of a rapport de force [balance of power] that was rooted in syndicalisme de combat [a fighting unionism] that is clearly important to consider right now within the broader union movement now under attack across Canada.

Q2: How did the Left outside the student movement – community organizers, union activists, unaffiliated radicals and so on – respond as the student mobilization grew?

There were some really beautiful responses. Mères en colère et solidaires [Angry Mothers in Solidarity] is a great example. This network attended many different actions and protests to represent the mothers of students on strike on the streets. Often Mères en colère et solidaires would vocally and also physically oppose the moves of police to shut down or attack student actions. Their presence was symbolically important but also tactically critical.

Another really, really important example was Profs contre la hausse [Teachers Against the Hike], which mobilized profs at both a college and university level outside of traditional teachers unions, although many people within the network were officially members of Fédération nationale des enseignantes et des enseignants du Québec (FNEEQ) [The National Federation of Teachers of Québec]. Although unfortunately FNEEQ, like most traditional unions in Québec society, did little in regards to street action to support the strike. Many unions issued excellent statements and made symbolic donations, which was important. But in terms of a street presence at critical moments, the unions didn’t step up to the extent that was possible given the institutional resources involved.

So within this context Profs contre la hausse was very important and responded in a meaningful way to the strike. One example that comes to mind was the strike defence pickets at Collège Lionel-Groulx when the Québec government was trying to break the strike by force by sending in Sûreté du Québec (SQ) [Québec provincial police] officers to break up joint student and teacher picket lines. There was a battle at Collège Lionel-Groulx where the SQ unleashed chemical sprays and hit picket lines that included many members of Profs contre la hausse that had organized buses from downtown to the college for strike supporters. I found the intervention of Profs contre la hausse on this day both decisive politically but also moving because it illustrated the broad nature of groups which were engaging with the strike on the streets.

More broadly speaking, I think what was really positive about the strike was that it shook apart unhealthy, informal hierarchies within the radical left networks. It opened up a great deal of political space and empowered many people to call for street actions autonomously. It provided the space for many to feel an empowerment to not wait for already established groups or organizations to call for actions – not only in relation to the student strike but also on the many other issues that the strike movement began to address – the environment, workers’ struggles, migrant justice. So this opening of political space sustains until today and is very politically healthy in my opinion.

Q3: Could you say some more about that?

I think that Québec’s student strike opened up a great deal of political space within grassroots activist networks in Québec. Also the strike created many new spaces, collectives and initiatives that sustain until today.

Broadly speaking the strike also had a democratizing impact on many activist networks in Montreal. It provided the context and space for a new generation of activists, many students, to fight neo-liberalism on the front-lines, collectively. Given the mass nature of the strike and the incredible mobilization work by ASSÉ, the strike was ‘populaire’ [popular] and relatively non-sectarian in nature. This was obviously so key to the mass participation in the movement.

I think that there is a constant challenge within activist networks to find ways to keep our organizing spaces open and welcoming. The strike was inspiring because radical political spaces and organizing processes were opening up, while also it was a moment where so many autonomous initiatives were sparked that radically diversified the activist political landscape in Québec. The strike was radical but open and inclusive at the same time because it was popular and mass in nature.

One example that comes to mind are the networks of people who consistently attended the night protests that began every evening at Émilie Gamelin square in downtown Montreal. Generally speaking the night protests began as a relatively autonomous initiative, a popular response to the growing state repression against the student strike, but also a way for many working people to join in solidarity protests.

Similarly the evening casserole [pots and pans] protests were relatively autonomous and were organized independently in different neighbourhoods around the city. A beautiful thing that I remember at many of night demonstrations and casserole actions was that you could see so many people connecting, talking, meeting each other in ways that I had never seen before at such a scale during protest actions.

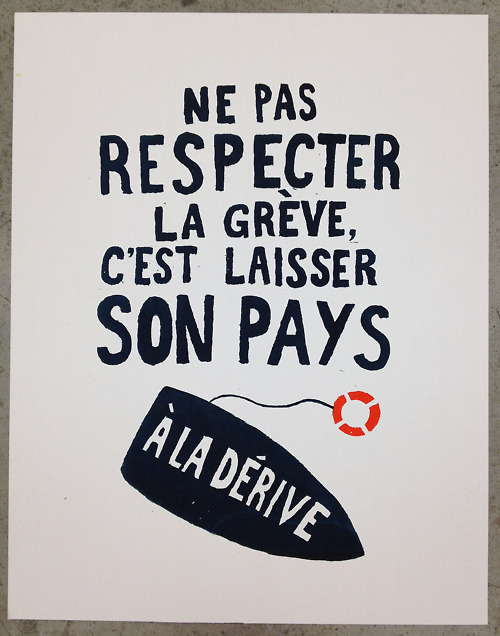

On the artistic front, there were initiatives like Fermaille, a literary project launched by literature students and friends around UQAM during the strike. Also the École de la Montagne Rouge was launched by design students at UQAM in response to the strike, a collective project that resulted in some of the most iconic imagery from the student revolt in Québec. Certainly the mass energy and creative spirit of the grève générale illimitée [unlimited mass strike] in Québec inspired these projects. Radical artist networks were also rapidly expanding and so many people felt emboldened by a sense of urgency to express what was happening on the streets without having to get anyone’s permission or prior acknowledgments. This was beautiful artistically and also politically.

Q4: How do you think the movement has affected the politics of the radical left in Québec?

On a broad level the student strike reasserted the idea that demanding the impossible is possible, that reform- or negotiation-based activism can only go so far, and that popular action is key to creating meaningful social change. Certainly there were many thousands of people engaged in different levels of activism with a belief in revolutionary change before the strike, but the strike radically widened the number of people willing to engage with activism while also it reaffirmed the spirit of many long-time activists. Québec’s student strike will have a longstanding impact not only on the radical left in Québec but also politics more broadly. In a sense the strike reasserted street politics. Protest continues to play a key role in shaping Québec society broadly speaking.

Q5: Are there any other political lessons you think the strike offers?

I think that there are so many possible responses to this question, well actually thousands and thousands from all the people who joined the movement. I have been thinking about this a great deal. One thing that comes to mind is organizational process.

Given that the student strike was rooted in ASSÉ and many other organized student groups, the organizational foundations for the strike were in many ways rooted in union structures. The strike mandates carried by students on to the streets were generally voted on in general assemblies and mass meetings, a form of popular democracy. I think that this take on union organizing is really important to highlight today because non-student unions in society, workers’ unions are failing to mobilize that same energy, vibrancy on the streets. Increasingly workers’ unions are focused on negotiating with power not re-imagining power and society, which under neo-liberal austerity economics is so important. The Québec student strike was so inspiring to so many people because it was rooted in syndicalisme de combat, revolutionary union organizing, rooted in the power of popular protest and action.

Given that the student strike was rooted in ASSÉ and many other organized student groups, the organizational foundations for the strike were in many ways rooted in union structures. The strike mandates carried by students on to the streets were generally voted on in general assemblies and mass meetings, a form of popular democracy. I think that this take on union organizing is really important to highlight today because non-student unions in society, workers’ unions are failing to mobilize that same energy, vibrancy on the streets. Increasingly workers’ unions are focused on negotiating with power not re-imagining power and society, which under neo-liberal austerity economics is so important. The Québec student strike was so inspiring to so many people because it was rooted in syndicalisme de combat, revolutionary union organizing, rooted in the power of popular protest and action.

In Québec and Canada unions face a crisis. There is a full-on assault on organized unions from the Conservative government that translates locally in Québec but also similarly across Canada. An example that comes to mind is the back-to-work legislation imposed on the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) in 2011. Another is the very recent back-to-work legislation imposed by the Parti Québécois against striking construction workers.

The response to this reality, this attack on unions as institutions and the rights of the people represented by unions, has been relatively soft. I think organized labour in general was certainly inspired by the Québec student uprising. We saw a major move from some unions to support ASSÉ, but unfortunately that support didn’t extend into actions on the streets. The question today is about how larger union structures could become more democratized and be rooted in the same spirit of syndicalisme de combat.

Q6: So you’re arguing that highly democratic, militant and solidaristic mass organizations are important, and that people should try to transform the existing bureaucratic unions. That sounds like a challenge to the way many anarchists in Québec, Canada and the US think about organizing. Is that how you see it?

Not exactly, but I see the point you are highlighting. I think the strike was a healthy challenge to radical left in general but also to traditional union structures which have an incredible amount of financial resources but are not stepping up in all the ways that could be possible against the very real Conservative attacks that are taking place.

There is a crisis facing major unions today in Canada and beyond, certainly within the US also.

At an event to launch at Bluestockings bookshop in New York City, I recall a really excellent conversation with some NYC activists who were working on the 99 Picket Lines project, a working group coming from the Occupy Wall Street organizing process. Activists who were organizing and supporting the 99 Picket Lines project were also working within some major US unions, specifically the American Federation of Teachers and the Communications Workers of America. I remember the discussion that focused on the inability of large labour unions in the US to respond to grassroots campaigns or actions and that these union activists were working within the larger unions while also organizing more grassroots actions. I really thought about that organizing reality in NYC for some time.

In the Québec context I think that the reason ASSÉ really was able to spark such a major strike process was due to many factors. One was that the organizing built up for many years. There was a large process of mobilization within many local unions affiliated to ASSÉ. The call for a grève générale illimitée was built over a long time and became stronger and stronger as it became clear that the Québec Liberal government was not going to back down on their move to impose a neo-liberal hike to university tuition fees at around 80 percent.

Certainly a critical element to the student strike was that the strike was organized within broadly representative student associations and unions, not only ASSÉ-affliated unions but also local unions associated to Fédération étudiante collégiale du Québec (FECQ) [Federation of College Students] and Fédération Etudiante Universitaire du Québec (FEUQ) [Federation of University Students].

A key move from ASSÉ in the lead up to the strike was to open up their organizing structure to student associations or groups not previously affiliated to ASSÉ. That happened through the creation of CLASSÉ (Coalition large de l’association pour une solidarité syndicale Étudiante, or Broad Coaltion of the Association for Union Solidarity among Students). In a sense CLASSÉ subverted traditional student union structures in Québec in the recognition that the mainstream political approach to the strike – that would focus on closed door negotiations with limited representation – clearly wouldn’t work in seriously combating the tuition hike, but also would be deeply undemocratic. So the general assembly model and the weekly congresses that took place during the strike via CLASSÉ were deeply important to both the grassroots momentum and energy of the strike.

A key move from ASSÉ in the lead up to the strike was to open up their organizing structure to student associations or groups not previously affiliated to ASSÉ. That happened through the creation of CLASSÉ (Coalition large de l’association pour une solidarité syndicale Étudiante, or Broad Coaltion of the Association for Union Solidarity among Students). In a sense CLASSÉ subverted traditional student union structures in Québec in the recognition that the mainstream political approach to the strike – that would focus on closed door negotiations with limited representation – clearly wouldn’t work in seriously combating the tuition hike, but also would be deeply undemocratic. So the general assembly model and the weekly congresses that took place during the strike via CLASSÉ were deeply important to both the grassroots momentum and energy of the strike.

So in a sense student activists were building on a process of radical institution-building within ASSÉ while also within the context of a strike, subverting the rigid nature of union representation, creating an open and democratic process through CLASSÉ. Certainly the broad nature of student mobilization was rooted in the fact that student votes toward the strike took place in a broadly representative fashion, through major general assemblies. Yes, this is a very different process than say a movement built, say, on the work of autonomous collectives or direct action committees. However it is essential to highlight that within the context of the strike autonomous collectives and various committees were totally essential in building the energy of the strike. Also important was that ASSÉ clearly refused to denounce the various direct actions that took place, there was debate about the extent to which ASSÉ could have been more supportive. However, broadly speaking, ASSÉ, or ASSÉ as an organizational process, never moved to try to politically alienate the small action initiatives that were taking place on a regular basis.

Two examples come to mind. One is the many actions of economic disruption that took place in the spring of 2012. Many of those actions involved CLASSÉ or ASSÉ members but were organized autonomously. Having that autonomy seemed critical to their success. Also the protest against police brutality that takes place every year on March 15 in Montreal was an important turning point in relation to the emergence of a broad sense that a social crisis, rooted in mass and unregulated street mobilizations, was emerging in Québec. This was an important moment because the annual protest against the police was major. There were thousands, including many, many striking students. And the fact that this autonomous protest was supported by ASSÉ – in that it was endorsed by ASSÉ, while it was organized autonomously – illustrated clearly that the movement in the spring of 2012 was larger than one union or specifically the student strike.

On the point of the role that unions played in the spring 2012 protest uprising in Québec, yes, student union structures were essential. However, the energy and creativity of grassroots autonomous actions were also central. The combination of both of these different processes that were deeply interacting in many ways was essential to the grassroots power of the strike.

Stefan Christoff is a Montreal writer, musician and community activist who recently published Le fond de l’air est rouge, a collection of texts about the 2012 Québec student uprising. Written between spring 2011 and summer 2012, this series of articles includes firsthand accounts of the incredible street protests in Montreal and reflections on the student strike within the context of Québec revolutionary history. It can be found here.