In 2012 Quebec has been shaken by the most important social movement in the Canadian state [1] since the 1970s. What began as a strike by students in Quebec’s universities and Collèges d’Enseignement Général et Professionnel (CEGEPs, which most young people attend after high school) against a major increase in university tuition fees – part of capital’s international austerity drive — has become a broader popular movement against the government of the Quebec Liberal Party (PLQ), headed by Premier Jean Charest, and against neoliberalism.

Universities in Quebec Society

To understand this movement, we need to look at the place of universities in Quebec society. The Canadian constitution makes education a responsibility of provincial governments. Before the 1960s, only a tiny percentage of the francophone majority in the province of Quebec attended university; university education was more common for members of the anglophone minority, whose universities were better-funded. At the time, the capitalist class in Quebec was largely anglophone – one feature of the national oppression of Quebec within the Canadian state. In the 1960s, a section of the francophone middle class launched an effort to modernize Quebec society that became known as the “Quiet Revolution.” One of its key features was the creation of a secular education system including new francophone universities that charged low tuition fees. This reform was linked with popular aspirations for national self-determination in an era that also saw a high level of working-class struggle. Accessible university education continues to be widely seen in Quebec as a valuable distinguishing feature of the Quebec nation.

Participation in post-secondary education grew rapidly in the 1960s. A vibrant student movement emerged, as it did in so many other countries in that era. Thanks to student activism including strikes in 1968, 1974, 1978 and 1986, tuition remained frozen between 1968 and 1990. The government succeeded in raising tuition in 1990 but its attempt to do so again in 1996 was beaten back by a resurgent student movement (though tuition for international students and other student fees were increased). In 2005 an attempt to convert over $100 million of student grants into loans was met with a partially-successful student strike.

In March 2011, the PLQ government announced a tuition increase of 75% over five years, beginning in 2012. The move was part of the government’s effort to advance neoliberalism in Quebec by introducing new fees for public services and raising existing ones. In Quebec neoliberal ideology isn’t accepted as “common sense” – especially in the working class — to the same extent that it is in the rest of the Canadian state. In the words of its finance minister, the Charest government aims to carry out a “cultural revolution.” It wants to replace the belief that people have a right to access public services funded by progressive taxation with the principle of “user pay.” Elements of the student movement had been preparing for mobilization since rumours of a large tuition increase first surfaced. The announcement spurred them into action.

The Student Movement

Quebec university and CEGEP students are organized into associations, facilitated by a legal framework with no equivalent elsewhere in the Canadian state. In Quebec there is a strong decades-long tradition of students organizing in very democratic and participatory ways through the general assemblies of their associations. Local associations may choose to affiliate to a Quebec-wide organization, of which there are four. The Association pour une Solidarité Syndicale Étudiante (ASSE), founded in 2001, promotes militant and democratic left-wing student unionism, in contrast to the others. In December 2011, ASSE formed the Coalition Large de l’Association pour une Solidarité Syndicale Étudiante (CLASSE), which student associations not affiliated to ASSE could join if they accepted its platform and highly democratic way of functioning. CLASSE was intentionally designed to coordinate a student strike and has been a tremendous success. It is currently made up of 65 associations with a combined membership of 100 000.

Student associations began to hold general assemblies to discuss the call for a strike. The strike began on February 13 and soon spread through universities and CEGEPs across Quebec. Participation was strongest in Montreal (Quebec’s largest city) and weaker in Quebec City (the capital city).

The most common form of action was not attending classes and organizing picket lines to prevent people from entering buildings or classrooms. In March, CLASSE passed a motion in favour of actions to disrupt the economy and the state, leading to “manif-actions” in which students took their struggle off campus and carried out blockades of government offices, courthouses, bank buildings, bridges and other targets. Students also marched in support of locked-out Rio Tinto aluminum smelter workers in the town of Alma, joined with other groups protesting austerity measures and protested the government’s plan to “develop” Northern Quebec, which is opposed by indigenous people and environmentalists. Art interventions and other cultural expressions of the movement gave the strike a growing public presence. The movement’s symbol, a red square (first used in 2005, because higher tuition would put students “squarely in the red”), was soon being worn by tens of thousands of people and made visible in other ways on the streets and online.

On March 22, the number of strikers peaked, with around 300 000 of Quebec’s 400 000 university and CEGEP students on strike that day. That same day – chosen consciously to refer to the May 22nd Movement which played a role in France’s massive student and working-class revolt of 1968 – saw a demonstration of some 200 000 people in Montreal (to put this in perspective, Quebec’s population is about 8 million). This took the movement to a higher level, with more students voting to take ongoing strike action. Students usually met weekly in general assemblies to decide whether or not to continue to strike, though some associations voted for unlimited strike action. Support for the strike remained much stronger among francophones than anglophones. People who experience racism have been underrepresented, highlighting the need to strengthen anti-racist education and action in the movement.

On April 14, CLASSE’s demonstration against both the Charest government and the very right-wing Conservative Party federal government of Prime Minister Steven Harper, called under the slogan “For a Quebec Spring,” was a real success. This was followed on April 22 with a huge Earth Day demonstration, where anger at the ecologically destructive actions of the Quebec and federal governments and major corporations was notably combined with support for the students’ cause and their anti-neoliberal militancy.

In an attempt to divide a movement that showed no signs of faltering, the Quebec government excluded CLASSE from its talks with student organizations. However, unlike in 2005 when they had agreed to a settlement rejected by the militant wing of the strike movement, the leaders of the other federations responded by maintaining a common front and withdrawing from negotiations. Charest then offered to spread the tuition increase over seven years rather than five. This was widely seen as an insult, and marches began to take place in Montreal every evening. Violent police repression at a demonstration outside a PLQ meeting in the small city of Victoriaville on May 4 was followed the next day by the announcement of a tentative deal to end the strike, brokered with the aid of the top officials of Quebec’s three trade union federations. When put to a vote the deal was massively rejected by students.

Having failed to demobilize the movement by depicting students as spoiled brats and offering insubstantial concessions, Charest turned to repression. The government rushed a special law, Law 78 (now Law 12), through the legislature in full knowledge that some of its provisions contravene the Quebec and Canadian charters of rights. This law bans demonstrations near universities and CEGEPs, declares demonstrations illegal if they are not registered in advance with the police, orders a resumption of classes in mid-August and imposes heavy fines for individuals or organizations that transgress the new rules. Municipal government followed up with restrictive bylaws of their own.

The Movement Broadens

This was a turning point. Instead of putting down the movement, Law 78 became the trigger for a transformation. What had been a student movement supported by a significant minority of the population became a broad social movement against the PLQ government. Already widely seen as corrupt and subservient to big business, the PLQ’s attack on civil liberties and student protest spurred many more people to act. On May 22, the 100th day of the strike, demonstrations took place across Quebec. Some 250 000 people marched in the rain in Montreal. This was followed by nightly “casserole” protests (in which people bang pots and pans) in the neighbourhoods of Montreal and Quebec City and other cities and towns. In some neighbourhoods popular assemblies began to meet. Mass arrests did little to stem the tide of defiance and solidarity.

Although some students and community activists had been calling for a “social strike” against the government, up to this point union support for the students had mainly been limited to giving money and participating in demonstrations (across the Canadian state labour law puts tight restrictions on strikes, including a prohibition of political strikes). After Law 78, discussion of solidarity action spread among union activists. A number of federations affiliated to the Confederation of National Trade Unions passed motions in favour of a day of strike action, to the consternation of its top officials. Unfortunately, the labour left is much too weak to be able to translate that sentiment into action.

Despite the arrival of summer, when student involvement in the paid workforce increases, and a lower level of involvement at the grassroots of the student movement, demonstrations on June 22 and July 22 were still very large. CLASSE has organized a tour, with its activists participating in events across Quebec to discuss the struggle and their radical manifesto, “Nous sommes avenir,” which calls for a social strike (the English translation is entitled “Share our future“).

Into a New Phase

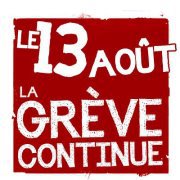

The movement is entering a new phase. Law 78 orders classes to resume at a number of CEGEPs during the week of August 13-17, but some activists are organizing a Block the Return to Class campaign independently of the official student organization structures, to minimize the weight of legal sanctions on the movement.

Charest has called an election for September 4. His gamble is that low voter turnout and the division of the anti-PLQ vote will maximize his chances of reelection. The PLQ faces its largest rival, the Parti Quebecois (PQ, a nationalist party that coats its neoliberalism with talk of fighting poverty and defending students’ and workers’ rights), the Coalition Avenir Quebec (a new aggressively neoliberal party) and Quebec Solidaire (QS, which unites much of the Quebec Left on the basis of anti-neoliberal reformism and support for Quebec independence). In the Canadian state, the candidate that wins the most votes wins in a constituency and the party that wins the most constituencies forms the government).

The election presents a challenge for the “Red Square” movement. Ruling-class strategists are undoubtedly hoping that the election will finally succeed in quelling the movement, allowing a PLQ or PQ government to claim that the disputed issues have been legitimately resolved and to decisively marginalize CLASSE and its allies.

The PQ is calling for a truce in the student struggle and, in keeping with its tradition of consulting with the leaders of unions and community organizations while it implements neoliberal policies, is promising a summit on university funding if it wins the election. Despite the PQ’s record in government, there is real pressure on students and others opposed to the PLQ to vote for the PQ as the “lesser evil” most likely to get Charest out of office.

While two of the other student federations (aligned informally with the PQ) are calling on students to vote, CLASSE is steaming ahead with its efforts to build the movement and prepare for the forced return to classes. CLASSE-affiliated student associations are holding general assemblies beginning on August 7, with a CLASSE congress scheduled for August 11-12.

A few words about the Quebec Left are in order. Its main political components are QS (which gathers together a range of forces, from social democrats to revolutionary socialists), anarchists, and social democrats who still haven’t quit the PQ. Many anarchists have done much to build the movement, both as students and community activists. Although QS proclaims itself a party “of the streets and the ballot boxes,” it is oriented and organized primarily for parliamentary politics.

QS has supported the student strike in a number of ways and many of its members have built the movement as activists. However, QS itself has not acted as an organized force to advance the struggle among students, in neighbourhoods and in workplaces. The movement has created a new opportunity to strengthen support within QS for anti-capitalist politics that treat mass direct action on the streets and in workplaces as the key to beating back attacks, winning reforms and ultimately transforming society. However, it’s not yet clear if people on the left wing of QS will be able to come together to do this.

Whatever happens in the next phase of the struggle, a number of things are clear. This remarkable movement has politicized Quebec society around the question of neoliberalism in a way that is without precedent in the Canadian state. It has radicalized many people, especially youth, many of whom have gained very valuable experience in mass mobilization and democratic self-organization.

Activists formed by the “Maple Spring,” as some have called the movement, will be critical for the future of the Left. The movement has also given Canadian activists both inspiration and ideas about how to struggle more effectively.

Footnote [1] This term, used by some socialists in Quebec, highlights that what’s usually called “Canada” is a multinational state made up of indigenous peoples, Quebec and Canada.

David Camfield is an editor of New Socialist Webzine. Thanks to Xavier Lafrance for comments.