This 56-page report illuminates the context for Angela Davis’ remarks in Germany last month, when she declared that the “refugee movement is the movement of the 21st century.” Patterns of displacement and migration reveal the unequal relations between rich and poor, between North and South, between whiteness and its racialized others.

Roots of the Migration Crisis

Aptly titled “World at War,” the UN report names wars and persecution as the drivers of forced displacement. Almost 14 million of the 59.5 million are newly displaced people over the past year, with an average of 42,500 people becoming refugees, asylum seekers, or internally displaced every single day primarily due to military conflicts.

The four-year civil war in Syria has created 11.6 million refugees, giving Syria the unfortunate honour of being the leading source country of refugees. Turkey, which neighbours Syria to the north, has become host to the world’s largest refugee population with almost 2 million refugees within its borders. Due to the ongoing occupation of Palestine by Israel, there are an estimated 5 million Palestinian refugees registered with a separate UN agency, UNRWA [the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East], in the West Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon.

While militarization and persecution are typically understood as primary forces of migration, forces of economic violence, climate change and gendered violence are all also causing displacement. The forced privatization and neoliberalization of subsistence farming has resulted in the loss of rural land for millions, particularly women peasants, across Asia, Africa, and South and Central America.

Though the UN report does not tackle displacements due to corporate interests and free trade deals, a recent study by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Huffington Post found that over the last decade, World Bank-funded projects physically or economically displaced 3.4 million people, forcing them from their homes, taking their land or damaging their livelihoods.

According to statistics by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, by the year 2020 there will be 50 million climate refugees. A day after the UN report on displacement, Pope Francis released his encyclical on climate change in which he articulates the connection between the climate, capitalist, and migration crises.

He writes: “Many of the poor live in areas particularly affected by phenomena related to warming, and their means of subsistence are largely dependent on natural reserves and ecosystemic services such as agriculture, fishing and forestry … There has been a tragic rise in the number of migrants seeking to flee from the growing poverty caused by environmental degradation. They are not recognized by international conventions as refugees; they bear the loss of the lives they have left behind, without enjoying any legal protection whatsoever. Sadly, there is widespread indifference to such suffering, which is even now taking place throughout our world.”

Border Militarization

“you broke the ocean in

half to be here.

only to meet nothing that wants you”

– Nayyirah Waheed

Despite the popular myth of First World benevolence toward refugees, 86 percent of refugees are actually in countries of the global South. Yet some of the most intense border enforcement policies – informed by long-standing racial fears of brown and Black migrants – are being undertaken by countries in the global North.

Immigration detention centers are the most visible sites of border enforcement policies, with migrant detainees forming one of the fastest growing prison populations around the Western world. In Canada, an immigration detainee being held in a maximum-security facility died June 11 in a local hospital after being restrained by officers. There have been at least 11 documented deaths in immigration detention custody in Canada since 2000. This week in Arizona over 200 migrant detainees at the Eloy Detention Center launched a hunger strike in response to the death of José de Jesús Deniz-Sahagún, who was beaten by guards. In the US, 106 people have died in immigration detention centers since 2003, and since 1998, more than 6,000 migrants have died trying to cross the US–Mexico border.

Geographer Reece Jones documents how three countries alone, including the US and Israel, have built over 3,500 miles of walls on their borders. An estimated half of all displaced people are children and a fraction of these children – around 50,000 children – traveling as unaccompanied minors primarily from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador were apprehended at the US-Mexico border last year.

Other countries, such as those in Western Europe, have pushed their border outwards to create “Fortress Europe.” The EU spent about $2.2 billion US between 2007-2013 to fortify its external borders through naval surveillance. Such “prevention-by deterrence” strategies have received international condemnation, with Amnesty International declaring, “The human tragedies unfolding every day at Europe’s borders are neither inevitable, nor beyond the EU’s control. Many are of the EU’s making. EU member states must, at last, start putting people before borders.”

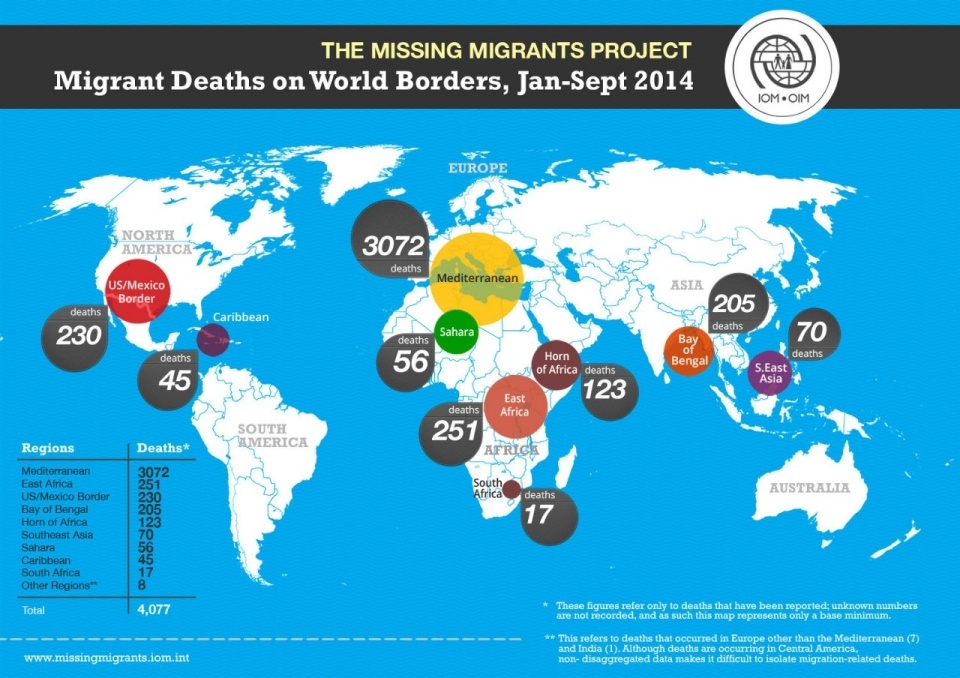

The International Organization for Migration has recorded 40,000 migration-related deaths around the world since 2000. Since that year, over 22,000 migrants have lost their lives trying to reach Europe. In the 2014 alone, over 3,000 migrants died in the Mediterranean, while this year over 800 died off the coast of Libya in a devastating boat wreck in April.

Recently, some European politicians suggested military operations to intercept and destroy boats transporting migrants and refugees off the coast of Libya. Perversely, these interventions were justified as humanitarian ones to target human smugglers, deemed modern-day slave-traders. Hundreds of academics immediately challenged this putatively progressive rhetoric, writing: “To attempt to crush [people-smuggling] with military force is not to take a noble stand against the evil of slavery, or even against ‘trafficking’. It is simply to continue a long tradition in which states, including slave states of the 18th and 19th century, use violence to prevent certain groups of human beings from moving freely.”

Indeed, border militarization policies make migrants’ journeys precarious and perilous. Bodies battering onto the shores and blistering in deserts may invoke sympathy and international discussions on how to “manage” the fatalities, but rarely do they invoke our collective sense of complicity and responsibility for migrant displacement and death. Geographer Mary Pat Brady describes migrant deaths as “a kind of passive capital punishment” where “immigrants have been effectively blamed for their own deaths.”

It is not a coincidence that migrant deaths are increasing every year, or that they happen at all. Migrants are dying at borders and in detention centers precisely because militarized borders and exclusionary immigration policies are intended to make their bodies, journeys and humanities vulnerable and expendable.

Harsha Walia (@HarshaWalia) is a South Asian activist and writer based in Vancouver, unceded Indigenous Coast Salish Territories in Canada. She has been involved in community-based grassroots migrant justice, feminist, anti-racist, Indigenous solidarity, anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist movements for fifteen years. She is the author of Undoing Border Imperialism.

This article was slightly adapted from the teleSUR orııgınal publıshed here. If you intend to use it, please cite the orıgınal source and provide the teleSUR lınk.