It’s great that more people on the U.S. left are embracing a politics of social class. But too many supporters of class politics still argue as if working-class struggle is separate from struggles against sexism, racism and other forms of oppression, or treat struggles against oppression as not all that important.

We can see this in the way some on the left criticize “identity politics.” In the wake of Donald Trump’s win, Bernie Sanders’ call to “go beyond identity politics” got lots of attention. Writing in Jacobin that “Identity politics can only get us so far,” Roger Lancaster argues for “an inclusive and universalist socialist program” because of the limits of demands by communities of “marginalized people” “for autonomy or for rights and recognitions.”

Similar arguments crop up in other countries too; it’s not just a U.S. thing. But it’s time for people on the left to stop arguing about “identity politics” in this way.

The first problem is that the meaning of “identity politics” is far from clear.

As Richard Seymour helpfully notes, the right uses the term to mean “any concession whatsoever to the idea that anyone other than white bourgeois men are ‘created equal.'” Used this way, it’s “part of a whole vocabulary including ‘thought police,’ ‘politically correct,’ and ‘liberal elites,’ whose main intention is to undermine the legitimacy of liberal and left politics,” as Linda Burnham argues.

Seymour adds that “a wing of the liberal center” uses “identity politics” “to criticize what they think of as the overly clamorous and over-hasty demands of women, gays, African-Americans, migrants and others for justice.”

These meanings propagated in the mainstream media are by far the most influential ways the term is understood. No wonder, then, that some people who experience racism, sexism, heterosexism and other forms of oppression identify “identity politics” with their struggles against the specific ways in which they’re harmed.

This is reason enough for people who mean something different than these understandings of “identity politics” to find another way of talking about it. “Identity politics” isn’t like “working class” or “socialism”–terms with highly contested meanings that we have to stick with because today we don’t have better words to use to communicate these ideas.

But the problem goes a lot deeper than terminology. Sanders called for Democratic candidates–“Black and white and Latino and gay and male”–with the “guts to stand up to the oligarchy,” who will “stand with…working people,” who understand how many people’s income and life expectancy are declining, and who get that many people can’t afford health care and college.

Lancaster is more radical: he praises the “original, radical outlooks” of the Black, women’s and gay and lesbian movements of the 1960s and 1970s. However, the content of the “inclusive and universalist socialist program” he contrasts with “identity politics” isn’t clear. He observes that what “socialist and working-class movements have usually demanded” are such things as “universal health care, free education, public housing, democratic control of the means of production.”

What both these lines of argument have in common is the idea that the left should champion a universalist politics instead of “identity politics”–and that universalist politics don’t include demands directed specifically against racism, sexism, heterosexism, settler-colonialism and other kinds of oppression.

Action against gender violence, free contraception, free abortion on demand, free public child care, a federal and state jobs program for economically marginalized Black people, permanent resident status for all immigrants, full legal equality for queer and trans people, self-determination for indigenous nations – these and other reforms to weaken oppression are downplayed or sometimes even excluded as “particular” “identity” demands.

This approach “not only presumes that class struggle is some sort of race- and gender-neutral terrain but takes for granted that movements focused on race, gender or sexuality necessarily undermine class unity and, by definition, cannot be emancipatory for the whole,” as Robin D.G. Kelley argued 20 years ago.

The history of struggles against oppression disproves those notions. The abolition of slavery in the U.S. inspired organizers for the rights of wage workers and women. “As slaves acted to change things for themselves, horizons broadened for almost everyone,” notes David Roediger.

The liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s loosened the grip of ruling-class ideology on U.S. society and influenced some of the broader struggles of workers and students of the time. The May 1 “Day Without Immigrants” protests of Latinx people in 2006 showed that political strike action is possible in the U.S.

Today, Black Lives Matter is encouraging some people who don’t experience racism to organize and fight for change. As we saw at Standing Rock, Indigenous land defenders are mounting some of the most effective resistance to capitalist energy industry projects that would make climate change even worse and contaminate water sources.

This history demonstrates that the freedom struggles of the oppressed can advance unity among workers by chipping away at material inequalities and reactionary ideas that divide the class. They’ve shown other people the power of militant collective action.

They’ve also inspired some who receive relative advantages because others are oppressed–men, white people, straights–to question our role and join in the struggle, leading us to recognize that perpetuating oppression is wrong and strengthens our enemies, and that these movements are ultimately about our freedom, too, as many of the demands in the platform of the Movement for Black Lives make clear.

Yes, socialists need to fight for demands like free education, dramatic action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions along with a just transition for workers negatively affected, and single-payer health care in the U.S.

But for socialist politics to be truly universal, they have to do more than advance such demands and link them to a vision of transforming society. We must also propose measures that specifically target different forms of oppression. That’s the best way to put the old workers’ movement slogan “An injury to one is an injury to all” into practice today.

To shy away from such measures because they’re unpopular among some of the people we want to organize is to avoid the hard work involved in forging unity in societies in which the working class is deeply divided and oppression is still very real in spite of gains in legal rights and cultural norms.

When carpenters union officials report workers without status to ICE; when many union leaders were on the wrong side at Standing Rock; when many white people act as if people of color are a threat to them; and when cis women and trans people are routinely denied control over their bodies; “race-blind” and “gender-blind” politics won’t help us get where we need to go.

Unity built on the foundation of such politics will be fragile and shallow. It will always remain vulnerable to divide-and-conquer tactics used by employers and politicians.

None of this means that a politics whose aspirations for oppressed people don’t go much beyond cultural recognition and fair representation in the power structure of neoliberal capitalism aren’t a problem. They are, as the records of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton reveal so clearly.

Some supporters of these politics opportunistically use insinuations about Sanders and “Bernie Bros” being supposedly hostile to women and Black people to smear anyone who criticizes the Democratic Party establishment from the left. But attacks on “identity politics” in the name of a “universalism” that underestimates the importance of oppression or that doesn’t explicitly take on oppression in every form aren’t the way to persuade people swayed by that kind of liberalism to embrace socialist politics.

, a socialist activist in Winnipeg and author of We Can Do Better: Ideas for Changing Society, comments on a discussion on the left about the place of struggles against oppression in the fight for socialism.

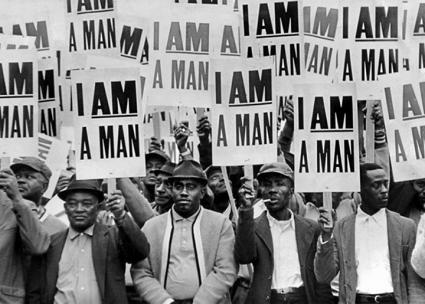

Photo: Sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, fighting for civil rights and union rights in 1968.

This article is originally appeared on socialistworker.org